Winners Take All, the third book from former New York Times columnist Anand Giridharadas, has created both great interest and, it seems, some confusion. Reviewers who complain that the book “bashes the overclass”, and implore us to “remember that there are winners who act ethically, too” may have missed the point, or a some good deal of it. No doubt there are winners who act ethically, but, while Winners Take All does indeed scrutinise, and yes criticise, present-day Western elite philanthropic practise (the subtitle is ‘the elite charade of changing the world’, after all), it has a broader, deeper purpose than simple class warfare. The books animating spirit is, it seems to me, to provide a critical exposition of modern elite power in America: its structures, its manifestations, its control of narrative form and scope, where it resides and how it entrenches and embeds itself. As such, it is an almost Gramscian work, such is the focus on the hegemonic power of present-day elite networks. Philanthropy is but the expression of these structures, whose roots reach deep into the economy, and, indeed, society. This should not be a controversial point: as Giriharadas says in the (unusually interesting) acknowledgements to Winners Take All, his target in the book is not philanthropy per se but, more specifically, its role as an “apparatus of justification” (a phrase he borrows from Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century) for elite power structures. And, in one of the books most illuminating passages, his analysis of Andrew Carnegie’s essay ‘Wealth‘, published in 1889, underscores again that the target for Winners Take All is not ultimately philanthropy, but the damage done by capitalist paternalism and excess, and the risks of putting profit before people. His comments in a recent podcast reveal his thinking:

“We talk about doing good, but we never talk about doing less harm. We talk about giving back, but we never talk about how much these people take, and the structures of taking. We talk about changing the world, but we never talk about all the ways in which they are shoring up the status quo that benefits them and predictably, reliably shuts other people out”

The book began life as a speech given by Giridharadas in 2015 at the Aspen Institute, where he was on the Henry Crown Fellowship programme, and whose reading list may be unique in including works from Gandhi and the former General Electric CEO Jack Welch. In the book, Giridharadas hangs his themes on several hooks, building the narrative through the voices of philanthropists, academics, senior Executives of major Foundations and economic development programmes, and others. One key idea is ‘MarketWorld’, the pro-free market conviction, common among elites, that no matter what the question, market-based solutions are the answer. Another is ‘Win-Win-ism’, the convention that social change must have an upside for all involved. A third is globalism, the strand of modern globalisation which has seen (and which often urges) businesses to be “agnostic about place”, where the simple, brutal imperative is to “[d]o each of your activities where it can best be done”. However, the book’s intellectual centre of gravity is the so-called ‘Aspen Consensus’, a set of beliefs neatly summarised by Giridharadas in the credo that “capitalism’s rough edges must be sanded and its surplus fruit shared, but the underlying system must never be questioned”. The Consensus enables – even encourages – capitalists to use any means they see fit to earn their fortunes. It also illuminates Giridharadas’ conviction that the winners in modern America have have pulled up the ladder of opportunity: as he said in a recent radio interview “it becomes a club…elites have rigged society to predictably, reliably, foreseeably shut a lot of people out of the opportunity to make a better life for themselves”.

If this seems somewhat radical, it should be no surprise: Giridharadas begins a chapter of Winners Take All with a quote (“the masters tools will never dismantle the masters house”) from the book of the same name by radical activist poet Audre Lourde. However, he omits the lines that follow this quote in the book: “[the masters tools] may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change”. And while a spirit of radicalism has a noticeable presence in Winners Take All, it is tempered by the fact that pointing out the paradoxes and hypocrisies of a period of fairly extreme capitalism is not in itself radical. This is itself a paradoxical aspect of some reaction to the book. Perhaps driven by talk of “plutocrats”, an “elite charade” and the books sustained examination of the beliefs of the HNWI class, Winners Take All has been portrayed almost as a work of anarchist philosophy. It is not, and, while Winners Take All is timely, highly competent and well-executed, it says a great deal of the tenor of current public debate that scrutiny of the underlying beliefs of the ‘haves and the have-yachts’ is taken to be such a radical act. I was reminded when reading Winners Take All of Professor Noam Chomsky’s observation that, despite publishing a book named ‘Our Revolution’ and being labelled a radical Socialist, many of Senator Bernie Sanders’ policies would have been perfectly familiar to (Republican) Dwight D. Eisenhower and his team and, indeed, would have seemed fairly moderate to many 1950’s American voters, familiar as they were with the New Deal and the idea of a significant role for Government intervention in public life. Today, after what Giridharadas has called a “30- or 40- year war on the very idea of Government”, many people now perceive the role of the public sector differently. But to my mind, to call, as Winners Take All does, for a re-energised, revitalised civic realm and reimagined, bolder role for Government with increased participation for younger people from a range of backgrounds is not radical. It is just common sense.

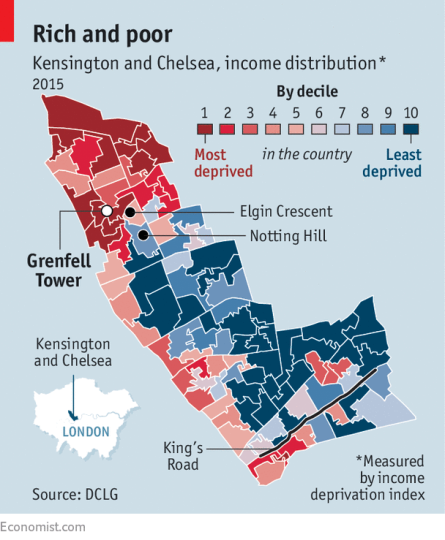

Given Giridharadas’ background as a journalist, it is to be expected that Winners Take All reads like a collection of high-quality long-form articles. With impressive skill, Giridharadas immerses himself in this world while at the same remaining distant from it. This is perhaps clearest in his account of a visit to the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI), where, with acute descriptions of the seminars, dainty finger food and earnest concern, Giridharadas captures a strong sense of a world which is entirely (and entirely willfully) separate from the one it proclaims to want to help, one where solutions to real-world problems are discussed by the great and the good, thousands of miles from the people whose lives the solutions will alter. Giridharadas skewers the CGI set with the odd caustic aside (“the party was full of the kind of people who say they ‘live between’ two places”). However, he is not unrelentingly critical, and shows an appreciation of the (apparently genuine) cognitive dissonance of those whose consciences nag them about the inequities and injustices of the status quo, but whose wealth and power depend on that same status quo remaining in place. “The people who ge to take advantage of the system, why would they want to change it?”, says one. “They’ll maybe give more money away, but they don’t want to radically change it”. This paradox is perhaps sharpest in the case of the Sackler family, whose pharma firm Purdue invented and (very aggressively) marketed prescription drugs, including painkiller OxyContin, which became a widely abused street-drug, and has been at the centre of America’s so-called opioid crisis. Despite the Sacklers $14bn fortune being built on sales of a highly-addictive opioid, and despite their having lobbied fiercely against regulation of its use, the family are best known today for their philanthropy. As Giridharadas notes: “[g]enerosity is not be a substitute for justice, but here, as so often in MarketWorld, it was allowed to stand in”.

As we pass the 10-year anniversary of the 2008 financial crisis, it is hard not to see Winners Take All in the light of work produced to describe that catastrophe. ‘Social silences’, described as an important causal factor in the financial crisis by Gillian Tett in her 2009 book Fools Gold, were important in reinforcing power structures before the crisis by keeping attention away from important issues by hiding them in under cover of silence. They are also central to the ‘Aspen Consensus’; Giridharadas has said he was aware of the attention-diversion of important issues he and his Aspen Fellowship group “were not talking about when we came together to talk about changing the world”. In its tone and narrative structure, Winners Take All bears some resemblance to Michael Lewis’s 2010 classic The Big Short. Both The Big Short and Winners Take All use a range of protagonists to tell their stories, and both engage the reader with direct, witty phrasing turning what could in the wrong hands be dry topics into important topics. Perhaps most directly however, Winners Take All can be seen as a bookend to Philanthrocapitalism by Michael Green and Matthew Bishop which, despite being released amid a financial crisis caused in no small part by financial institutions led by some of the world’s wealthiest individuals, was subtitled ‘How the Rich Can Save the World’. Winners Take All is an epic refutation of Philanthrocapitalism’s core tenet, which Giridharadas has tartly stated as being that “the people who broke things are the best qualified to fix them. The arsonists are the best firefighters”. While this thesis may have found favour in the Roaring 2000’s, times have changed. The Great Recession, Occupy, awareness of the ‘1% and 99%’ and Trump have shifted the tenor of the public mood in English-speaking countries, and the argument that elites must be left to run the show has, in important respects, run out of road. Part of the appeal of Winners Take All is that it rejects the notion that major social problems can be painlessly spreadsheeted away using McKinsey-like methods, or that corporations’ only responsibility is to make as much money as possible. For Giridharadas, the goal should be to give up the excesses of no-holds-barred free-market capitalism, not just give some back once the fortune is banked. The contrast with Philanthropcapitalism, and its starry-eyed homage to the possibility of elite philanthropy, could not be clearer.

For all its strengths, Winners Take All also has limits. Giridharadas’ decision to omit a ‘solutions chapter’ – or anything like it – may have merit, but does forego the opportunity to tie together the various narrative threads. It also precludes a discussion of Giridharadas’ (very sensible) suggestion, presented in interviews around the release of the book, to encourage talented students to take up roles in Government by forgiving the student debts of graduates who choose to go into public service, a shame as this is a credible policy proposal which merits attention. The omission of a ‘solutions chapter’ is compounded by Winners’ Take All’s narrow field of vision. While in his promotional interviews for the book Giridharadas speaks of the need to recognise the many “varieties of capitalism” across the world (a clear, though apparently unreferenced, nod to the influential 2001 book of the same name by Peter Hall and David Soskice), Winners Take All fails to mention any of the enormous range of ‘varieties of philanthropy’ practised across the world. The reader is left unclear as to what the alternative might be to modern American philanthro-capitalism, when the fact is that systems of generating and dispensing social good are legion, whether the religious practices of the Muslim zakat, Judaism’s tzedakah or Christian alms, or simple volunteering, whose ubiquity has led the Bank of England’s Chief Economist to point out that, taken together, volunteers constitute the second-largest workforce in the entire world after Chinese adults. While Winners Take All was clearly never intended to be a survey of mechanisms of (or even necessarily motivations for) donating money and time, it would have benefited from greater depth in displaying an awareness of other approaches to what we in the West call ‘philanthropy’.

Despite his not being mentioned in the book, the spirit of the work of historian Tony Judt flows through Winners Take All, in particular Judt’s final book, Ill Fares the Land. Judt, who died in 2010, was the very embodiment of the public intellectual, as opposed to the vacuous ‘thought leaders’ described so coruscatingly in Winners Take All, “who are willing to confine their thinking to improving lives within the faulty system rather than tackling the faults”. While Judt specialised in post-war European history, he was also a committed social democrat, and an eloquent, forceful critic of modern capitalism, saying that “[i]f modern democracies are to survive…they need to be bound by something more than the pursuit of private economic advantage”. When Giriharadas says “what is at stake is whether the reform of our common life is led by governments elected by and accountable to the people, or rather by wealthy elites claiming to know our best interests”, he channels Judt’s spirit. And his statement in the denouement of Winners Take All that “[e]conomistic reasoning dominates our age” strikingly resembles the firt words of Judt’s 2007 assertion (in ‘The Wrecking Ball of Innovation‘) that “[w]e live in an economic age…the new master narrative – the way we think of our world – has abandoned the social for the economic”. Given that Judt was one of the brightest and most humane voices of his generation this is a very good sign.

Winners Take All is as readable as it is informed, and displays throughout a journalistic knack for so effectively capturing the perspective and of an insider-outsider, (his phrase, again from the acknowledgements). The use of first-hand interviews and reportage connects the reader directly with situations that would otherwise seem distant, and the use of a range of characters humanises the rarefied world of power-brokers and high-achievers, which many will never experience first-hand. While it maintains a somewhat narrow focus and avoids suggesting potential solutions, Giridharadas’s sharp eye for detail and strong, principled stance make Winners Take All a satisfying and informative read. It is highly recommend.